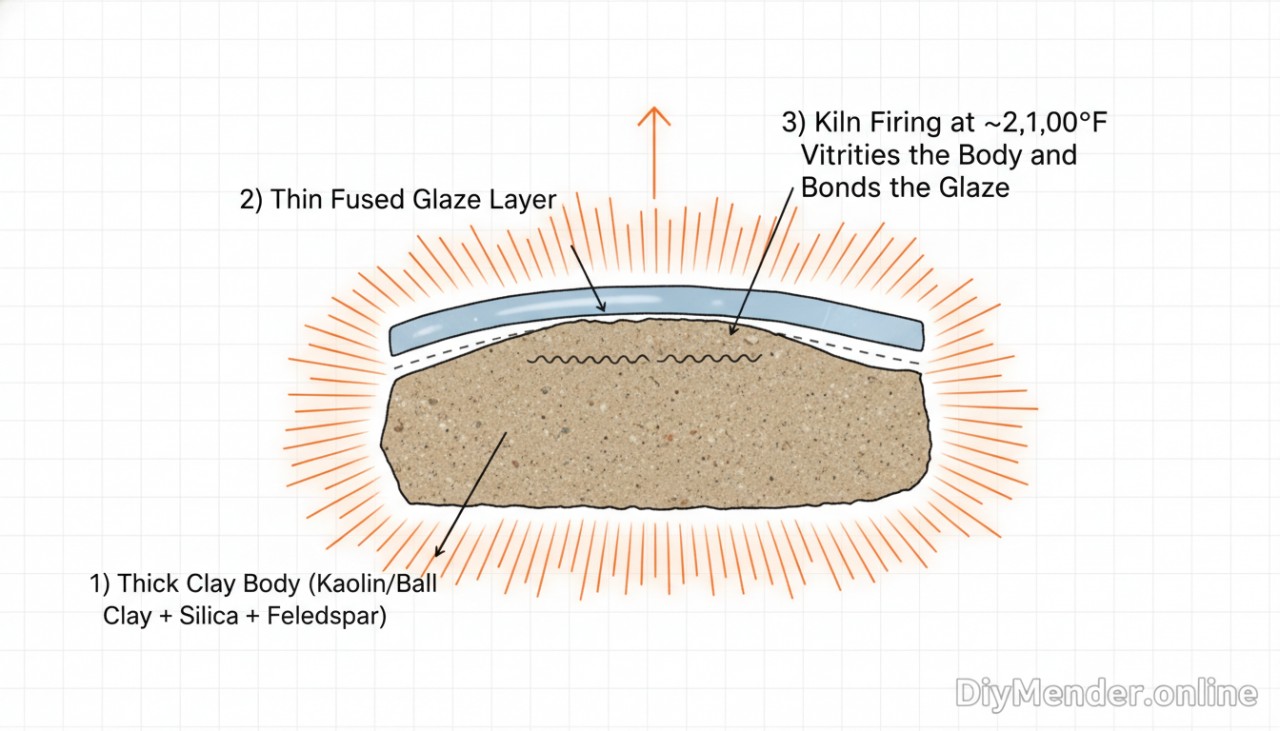

If you’re wondering what is fireclay sink made of, here’s the straight answer from a homeowner who’s installed a few: it’s a thick, vitrified ceramic body made from refined clays (mostly kaolin and ball clay) mixed with silica and feldspar, shaped in a mold, then coated with a vitreous glaze and fired at roughly 2,000–2,200°F until the clay and glaze fuse into a hard, nonporous shell. That high-heat fusion is why a fireclay sink resists stains, acids, and heat better than typical ceramic—and why it’s heavy and rigid, not flexible like stainless.

What It’s Made Of—and How That Changes Performance

Composition: manufacturers blend kaolin (for whiteness and strength), ball clay (workability), silica (reduces shrinkage and adds hardness), and feldspar (a flux that helps the clay vitrify). Water turns it into a pourable slip that’s cast into plaster molds to form the sink’s thick walls, often 1/2" to 1".

Glazing and firing: the green body is dried, sometimes pre-fired (bisque), then sprayed with a vitreous glaze. During the final firing above ~2,000°F, the body vitrifies—pores seal—and the glaze fuses to the surface. Done right, you get a single, glassy skin over a dense ceramic core.

Why this matters: vitrification is the secret sauce. It makes the sink nonporous (stain-resistant), chemically stable (resists acids/alkalis), and hard under compression. The trade-off is brittleness: it shrugs off hot pans and tomato sauce but doesn’t love dropped cast-iron skillets.

Why Fireclay Shines—and Where It Fails

Strengths: the fused glaze is slick and nonporous, so coffee, wine, and beet juice usually can’t soak in. The body handles high heat—setting a hot pot down won’t scorch it—and the thick walls damp noise better than stainless.

Failure modes: chips occur when a hard object strikes the rim or corners, fracturing the glaze and sometimes the body. Hairline crazing (spiderweb cracks in the glaze) can happen if the glaze and body expand differently, sometimes years later. Extreme thermal shock—dumping a full pot of boiling water onto a sink packed with ice—can stress the glaze, though normal cooking use is fine.

Fireclay vs Porcelain vs Enameled Cast Iron

Fireclay vs porcelain (vitreous china): both are ceramics with glaze, but fireclay is generally thicker and fired hotter for kitchen-duty abuse; porcelain is often used for toilets/lavs and can feel lighter. Fireclay’s thickness resists flexing under garbage disposals.

Fireclay vs enameled cast iron: cast iron has a metal core with a vitreous enamel coating. It’s also heavy and durable, but the metal can rust if enamel chips through. Fireclay is ceramic all the way through; a chip exposes white ceramic, not metal, but is still a chip.

Common Homeowner Mistakes I See

- Over-tightening the drain basket: compresses and micro-cracks the glaze around the drain. Hand-tight plus a bit—use plumber’s putty if approved by the maker or 100% silicone if not.

- No base support: apron-front fireclay needs a cradle or ledge support, not just silicone. These sinks can weigh 80–120 lbs empty.

- Leveling assumptions: cabinets out of level twist the sink and can lead to stress cracks. Shim the support perfectly flat.

- Abrasive cleaners and steel wool: they dull the glaze, making it more prone to metal marks and stains.

- Thermal shock tests: don’t dump boiling pasta water onto a sink full of ice “to see if it’s tough.” That’s how you get crazing.

Edge Cases and Limits

Matte glazes: stylish, but they show oils and can be harder to clean without visible swirl marks. Gloss hides more sins.

Colored glazes: good brands use lead-free, cadmium-compliant glazes (check certifications). Dark colors can show limescale; whites show metal marks more but clean up easily.

Garbage disposals: use vibration-damping collars. Fireclay won’t flex, so isolate the motor’s buzz or you’ll get a hum.

Hairline crazing: if it appears early, call the manufacturer; often a warranty issue. If it appears years later, it’s cosmetic more than functional but can harbor discoloration.

Installation Notes That Save Headaches

Support: build a pair of ledger rails or a full cradle inside the sink base. The sink should sit on wood, not hang from the countertop.

Reveal choice: negative, zero, or positive reveal at the countertop edge is aesthetic, but ensure the cutout matches the specific sink (fireclay tolerances vary). Dry-fit; these are hand-formed and rarely perfectly square.

Sealants: a bead of silicone between sink and counter is typical. Don’t rely on silicone for structural support.

Drain and accessories: most fireclay sinks use a standard 3-1/2" drain. If you’re installing a disposal, verify the flange seats flush on the glaze and don’t over-torque.

Care That Actually Works

Daily: rinse and wipe. Use a stainless grid to prevent pan impacts and to keep dishes off the glaze.

Weekly: a non-abrasive cleaner (dish soap, baking soda paste, or a non-scratch cream). For metal marks from pots, a dab of Bar Keepers Friend or a melamine sponge, used lightly, removes them without scouring.

Hard water: prevent scale by drying after use or use a vinegar spritz, then rinse. Avoid leaving rusting steel wool pads in the basin—they can leave orange stains (removable, but annoying).

Buying Checklist From a DIY’er

- Wall thickness and weight: thicker generally equals more durable. Tap it—dense sinks ring with a low, solid tone.

- Glaze quality: smooth, even, no pinholes or ripples at corners.

- Tolerances: expect minor dimensional variation; make sure the cabinet and counter fabricator see the actual sink before cutting.

- Warranty and certifications: look for lead/cadmium compliance and a clear crack/crazing policy.

Bottom line: a fireclay sink is made of refined clay, silica, and fluxes fused under extreme heat beneath a glassy glaze. That chemistry delivers a nonporous, heat-tolerant workhorse. Treat it like the rigid ceramic it is—support it well, avoid impacts and harsh abrasives—and it’ll stay handsome long after trendier finishes fade.